[mashshare]

By Tony Holler

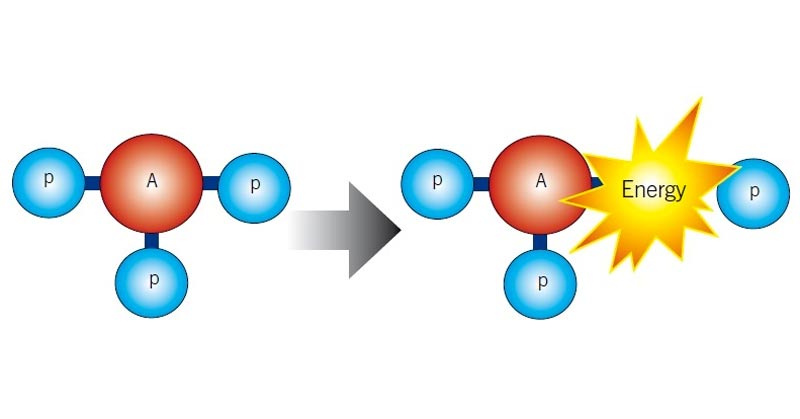

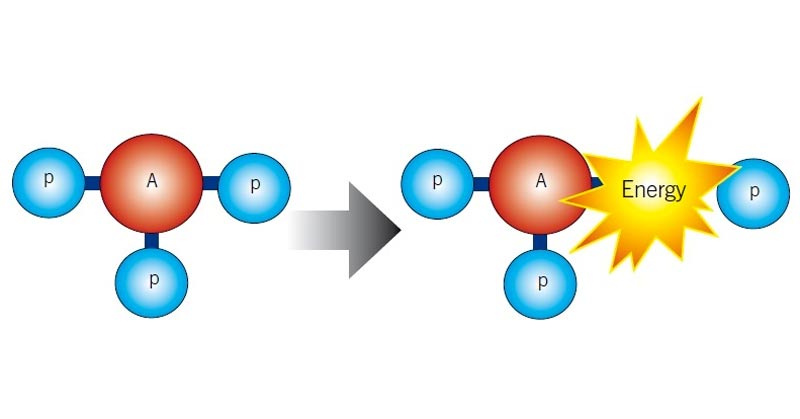

The alactic anaerobic system is the dominant source of muscle energy for high-intensity explosive exercise that lasts for 10 seconds or less. I refer to alactic training as “phosphate training” because the fuel for this first 10 seconds of high-intensity explosive exercise is the ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) which is readily available in muscles.

The lactic anaerobic system (glycolysis) is recruited after the ATP storage has been depleted (usually after ten seconds in well-trained athletes). We do “lactate workouts” once or twice a week starting February 8th. And, meets are considered lactate workouts.

Over the winter, I believe sprinters should develop a speed base, not an endurance base. We never do lactate workouts or aerobic workouts in the winter. We only do phosphate training (alactic). All training is high intensity for periods of less than ten seconds.

I share what we do for the benefit of others. We do what we do because it works for us.

At Plainfield North High School, we train after school from early December until early February. Our school day goes from 7:05 until 2:10, so we start at 2:30. The workout goes from 2:30 until approximately 4:15.

This year, 130 boys participated in our program at one time or another. The average attendance was typically 80 to 100. The program is non-mandatory and unfunded. I’m the head track coach and freshmen football coach at North. I run the sprint part of the workout. Our football coach, Tim Kane, manages the weight room activities. We’ve done this for ten years without pay, working together for our mutual benefit and the benefit of Plainfield North athletes. Everyone wins.

Tim and I don’t always agree, but we always find common ground. I am often asked how to change the mindset of a football coach. The stereotypical football coach is a paranoid, testosterone-riddled, hard-headed, Type-A personality who measures his life in first downs and turnovers. Transforming the mindset of a football coach is not an easy task.

Most head track coaches come from the cross country universe, making the unification of track and football programs nearly impossible. I’m thankful that Coach Kane sees me as a colleague, not an alien. The fact I’ve won 39 consecutive games as his freshmen football coach gives me some street cred.

For the distance coaches out there, our 40 distance runners run outside every day in rain, sleet, snow, and ice. High winds and cold temperatures are daily. Coach Andy Derks has created a culture where no culture had previously existed. Our distance runners train aerobically with speed work mixed in. Distance coaches build an aerobic base, sprint coaches build an alactic base (unless you are a disciple of Clyde Hart).

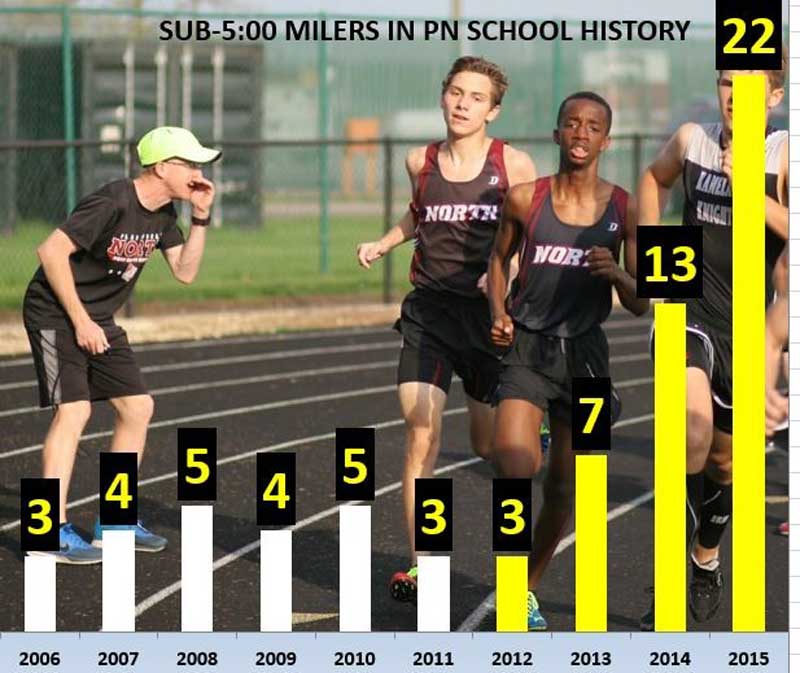

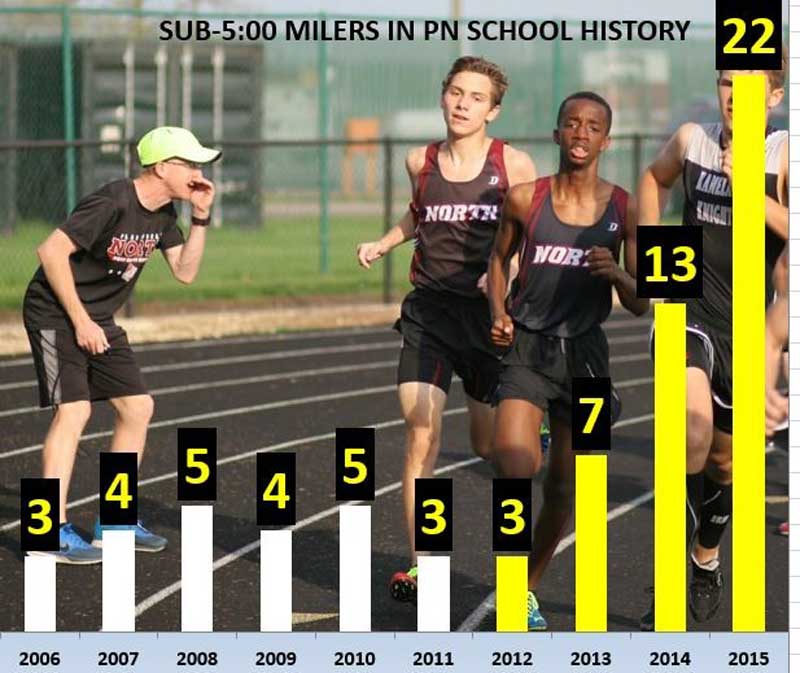

Figure 1. Coach Derks came to Plainfield North in 2012. Last year we had 22 guys run under 5:00 in the 1600. Our distance crew makes up about 40% of our track team. The other 60% percent of our team spend their time sprinting with me and lifting with Tim Kane.

In the weight room, we strength train Monday through Thursday. I have expressed my lifting philosophy to Coach Kane and he generally agrees.

Our varsity football players lift first, at 2:30. Fifty guys lift as a team. I would rather have all my sprinters in the 2:30 sprint group, but this is a compromise I make.

Coach Kane compromises too. No lifting is done on legs until Thursday. We take Friday, Saturday, and Sunday off. Some people call it a three-day weekend. I call it supercompensation.

Since the varsity football group does not include seniors who have graduated from the football program, my 2:30 sprint group will have some senior football players. In addition, I have freshmen football players, lacrosse kids, baseball players, and, of course, track athletes.

The first session lasts 45-50 minutes, and then our groups switch. From 3:20 – 4:15, I speed train the varsity football team.

On a given day, only 50% of the kids being trained are track athletes.

We start every day with sprint drills, probably the same drills you’ve seen everywhere. As another coach once told me, “Everyone does speed drills, but your kids do them better.” I believe this to be true. We never go through the motions. I refuse to call our opening session a “warmup.” In 17 years of doing this, I’ve never had an athlete get injured doing speed drills. Never. The speed drills done every day include A-skips, high-knees, butt-kicks, 5 box jumps, bounding, straight-legged bounds x2, butt-kick & reach (retro sprints) x2, and starts (2-point, 3-point, or 4-point hop & go). We are done in about 10 minutes.

On Mondays and Wednesdays, we sprint for time. Our field house has a 180m track with a six-lane straight-a-way. We have enough room to run the 55m in an indoor meet. On Mondays and Wednesdays, our kids run 40-yard dashes with a hand-held time. I’ve been doing this for 17 years and can’t give up on my comparative data. Our times are fast because of hand-timing, 2-point starts, and wearing spikes on a rock-hard track. Here is the kicker … we time the last 10m with Freelap (Pro Coach, 12 FxChips). With every run, I record two types of data, 40-yard dash and 10m fly. We run solo. I don’t believe in racing until track season. I want sprinters focused on their fundamentals and competing against themselves. I record, rank, and publish times.

We have two groups, the non-sprint-slow-guys-who-don’t-wear-spikes group, and the speedy-always-remember-their-spikes group. Group-1 is one and done; then they leave the field house. Group-2 runs three 40s.

When coaches hear that we run only three sprints, they are dumbfounded. What? Then what do you do?

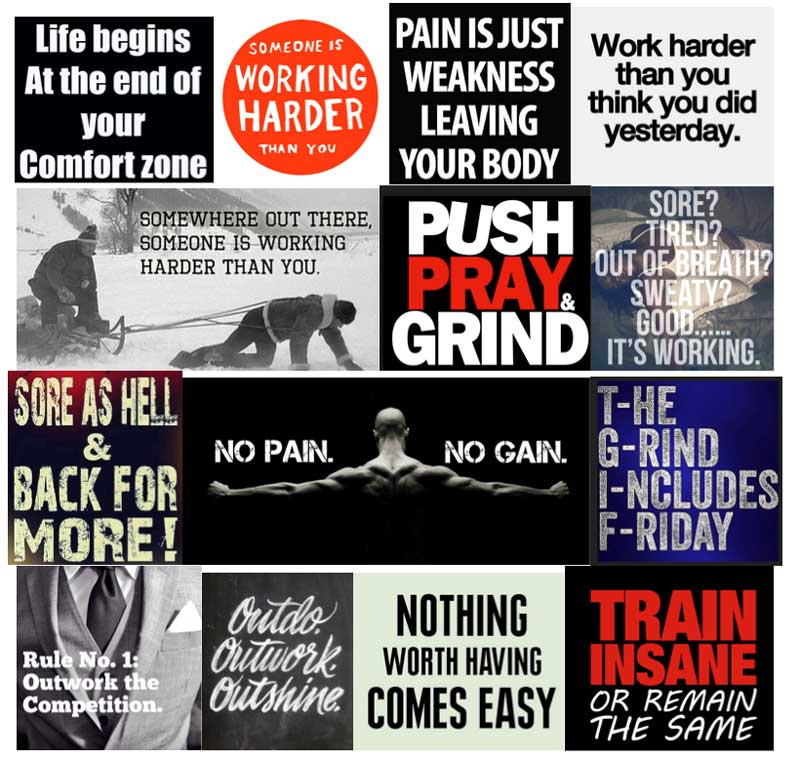

“Hard work beats talent when talent doesn’t work hard.” “Nothing worth having comes easy.” “There’s no substitute for hard work.” Coaches are addicted to quotes about work. If the mission of a coach is to get their athletes tired, fine … but don’t expect speed to improve.

Stupid coaches sometimes have the hardest practices. Focus is the key to speed, not hard work.

Figure 2. Don’t be this coach. Train smarter, not harder.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, we do X-Factor workouts. On these days, the football coach joins me. Like always, we do 10 minutes of speed drills. After speed drills, we do four different activities in the form of stations, rotating back and forth between the football coach and me. The only thing I’ve asked Coach Kane … please do things at top speed then allow for enough recovery to go top speed again. The easiest thing for any coach is to get their athletes tired and sore. “Any fool can get another fool tired.” Coach Kane will do agility work, multi-directional sprinting, short hurdles, and speed ladders. X-factor is a day to try new things (“x” stands for unknown). I do wickets, hip mobility, plyometrics, lunges, depth jumps, cat jumps, etc. Since football lifts legs on Thursday, X-Factor is a good way to end the week.

Remember, our program at Plainfield North is based on common ground. Would I prefer sprinting before lifting? Of course. Do I agree with training Monday through Thursday? No. I would prefer Monday-Wednesday-Friday. I am fundamentally opposed sprinters training when they are beaten and battered. We all make deals with the devil, and I will always make deals with football coaches.

My data justified my training philosophy a long time ago. I’ve been doing this for 17 years, and my athletes get faster. More important, talented athletes are attracted to my sprint program.

Data drives my athletes. Low-effort never happens in my speed training. No one forgets their spikes. I literally see my sprinters carrying their spike bag with them in the hallways. Backpack, cell phone, and spikes … the necessities.

At Plainfield North football players run track:

Plainfield North opened its doors in 2005-06 to only freshmen and sophomores. I became the first head track coach at North in 2006-07. Our first senior class graduated in 2008.

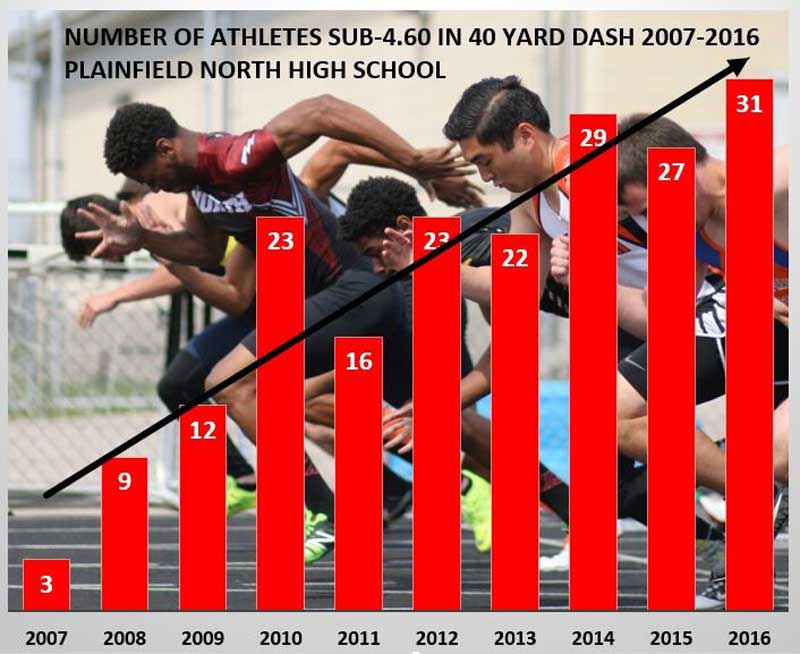

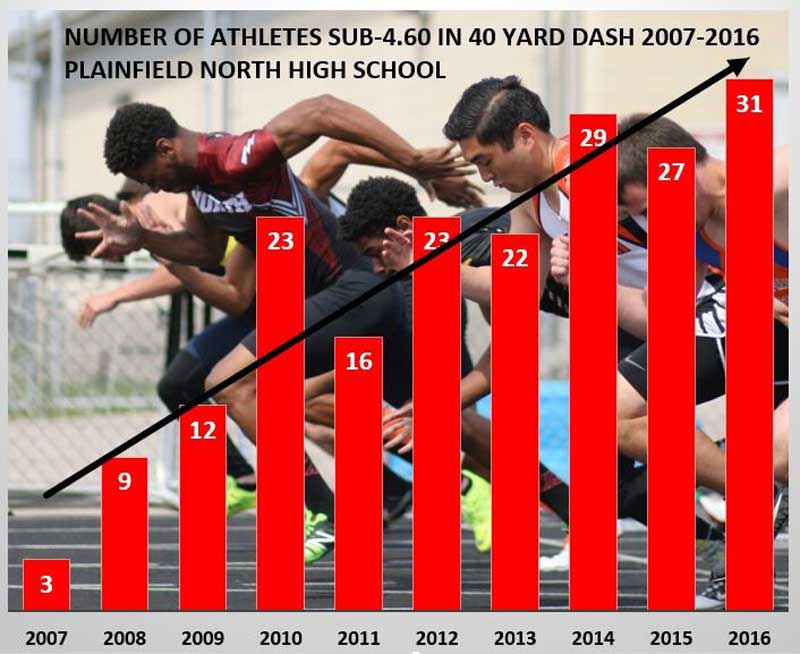

The graph below illustrates our ten-year progress towards creating a culture of speed. I brashly tell people that athletes at Plainfield North know their AFT (Average Forty Time) better than their GPA.

Figure 3. Number of athletes that ran sub 4.60 in the 40-yard dash by year.

Oddly enough, we qualified for the state 4×100 in 2007 in spite our overall lack of speed. It only takes four reasonably fast kids with great handoffs to run a decent sprint relay. If you question our impressive speed numbers, remember … we run hand-held 40’s with a 2-point stance with spikes on a hard track. The numbers are legit. If you time your 40s outside on turf without spikes wearing sweat pants and hoodies, your times won’t be as fast. Personally, I like fast.

In addition, the 40s timed in our winter workouts are always done in the same lane and same direction. Wind is never a factor because we run indoors. I’m the only person who times 40s. No manager or assistant coach will be trusted with the stopwatch.

It’s difficult for some people to understand why we post sprint times. The haters of the world will think we are being boastful. This could not be further from the truth. We simply post times to make times meaningful. Athletes crave competition. Athletes are starved for praise. In addition, coaches must demand quality.

Try this sometime. Tell an 8-year-old to run as fast as he can between two Freelap transmitters (yellow cones). Tell him his time. Then tell him that you will give him $10 if he can run faster. Have several kids cheer him on from both sides of his running lane (we call this “the gantlet”). I am 100% certain you will lose $10.

I did this once in speed camp. I had a young boy who ran several times above 2.00 in the 10m fly. Each time I encouraged him to SPRINT, but his times remained slow. When I attached meaning and significance to his sprinting, he ran faster. His best time improved from 2.03 to 1.57. When you record, rank, and publish, kids learn to SPRINT. Otherwise, kids just run.

Good track programs attract athletes. 24 of my 52 sprinters are newcomers. Check out the average 40 time and average 10m fly time for my top 11 newcomers.

When you add eleven guys like this to a good track team, the future looks bright. Kids love a speed-based track program.

We’ve had some bad luck with three of our top sprinters. Tim Donnahue was expected to take one of our sprint relay spots but broke his leg in Wrestling. Our two returning all-state athletes have had some senior bad luck as well. One has a hip-flexor injury and hasn’t sprinted since football. The other, our two-time MVP, has struggled on a daily basis to find food, transportation, and shelter. No one said it would be easy.

Figure 4. We return Zach Shelton (left) and DeVaughn Hrobowski (right) from our all-state sprint relay teams. This picture was taken at Sectional when we ran 42.07 in spite of this run-up handoff at the first exchange. Shelton and Hrobowski missed our winter training. Shelton was injured, Hrobowski spent the winter on the wrestling team.

Despite the bumps in the road, we have seen great improvement in most of our core sprinters. The numbers below indicate their average times last year compared to their average times this year.

The numbers also point out that we are an improved sprint group, at least in sprint depth.

We have tryouts for three weeks (Jan 19 – Feb 4). This is what it took to make our sprint group (slowest sprinter from each class, average 40-time and average 10-fly time):

Data allows us to highlight athletes who show incredible improvement. Celebrating these athletes, in turn, promotes track & field.

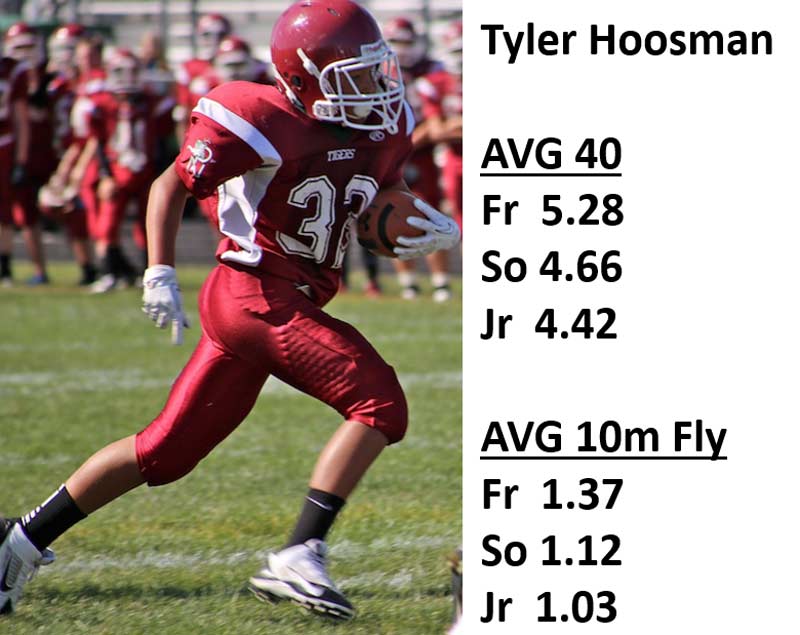

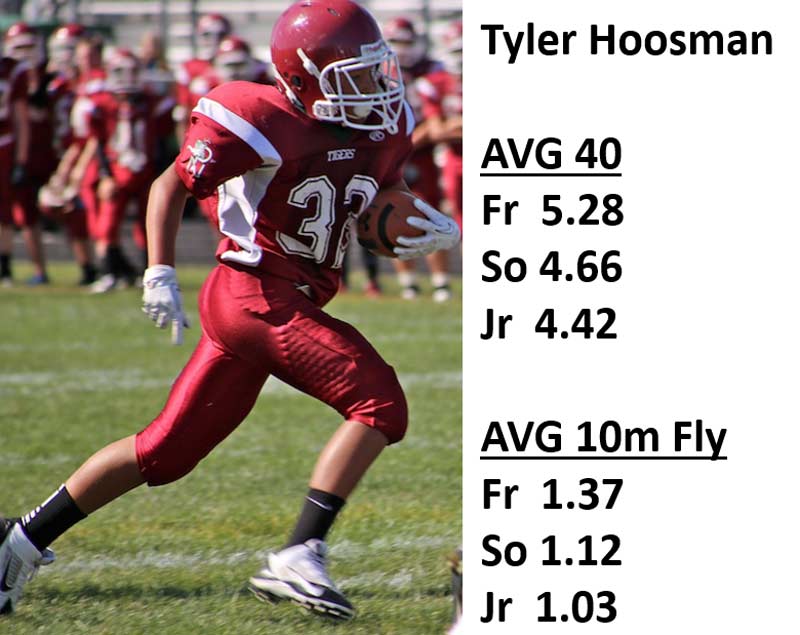

Tyler Hoosman is pictured below as a freshman B-team running back. Tyler went out for track his freshman year despite being our slowest sprinter. As a freshmen, Tyler ran the 100 in 13.00, the 200 in 27.9 and long jumped 16’8”. As a sophomore, Tyler obliterated those numbers running 11.92 and 24.38 while long jumping 19’10”. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to project amazing things this spring. Oh, and by the way, Tyler was our varsity’s leading rusher in his junior season. He returns next year.

Figure 5. Plainfield North Running Back Tyler Hoosman as a freshman.

Tyler Hoosman no longer looks like a B-team freshman running back. Tyler now looks like a sprinter. Not everyone will experience the incredible improvement of Tyler Hoosman, but if you don’t measure speed, you will never know.

Figure 6. Tyler Hoosman as a junior. Next year Tyler will dominate.

Run fast to get fast.

Train the alactic system (100% intensity, less than 10 seconds in duration).

Train smarter, not harder.

Recruit, Promote, Attract.

Record, Rank, Publish.

It works for us.

Please share so others may benefit.

[mashshare]

The post Record, Rank & Publish: 8 Weeks of Alactic Training appeared first on Freelap USA.

By Tony Holler

The alactic anaerobic system is the dominant source of muscle energy for high-intensity explosive exercise that lasts for 10 seconds or less. I refer to alactic training as “phosphate training” because the fuel for this first 10 seconds of high-intensity explosive exercise is the ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) which is readily available in muscles.

The lactic anaerobic system (glycolysis) is recruited after the ATP storage has been depleted (usually after ten seconds in well-trained athletes). We do “lactate workouts” once or twice a week starting February 8th. And, meets are considered lactate workouts.

Over the winter, I believe sprinters should develop a speed base, not an endurance base. We never do lactate workouts or aerobic workouts in the winter. We only do phosphate training (alactic). All training is high intensity for periods of less than ten seconds.

I share what we do for the benefit of others. We do what we do because it works for us.

At Plainfield North High School, we train after school from early December until early February. Our school day goes from 7:05 until 2:10, so we start at 2:30. The workout goes from 2:30 until approximately 4:15.

This year, 130 boys participated in our program at one time or another. The average attendance was typically 80 to 100. The program is non-mandatory and unfunded. I’m the head track coach and freshmen football coach at North. I run the sprint part of the workout. Our football coach, Tim Kane, manages the weight room activities. We’ve done this for ten years without pay, working together for our mutual benefit and the benefit of Plainfield North athletes. Everyone wins.

Tim and I don’t always agree, but we always find common ground. I am often asked how to change the mindset of a football coach. The stereotypical football coach is a paranoid, testosterone-riddled, hard-headed, Type-A personality who measures his life in first downs and turnovers. Transforming the mindset of a football coach is not an easy task.

No driven man hears unwanted counsel. – Janny Wurts

Most head track coaches come from the cross country universe, making the unification of track and football programs nearly impossible. I’m thankful that Coach Kane sees me as a colleague, not an alien. The fact I’ve won 39 consecutive games as his freshmen football coach gives me some street cred.

Distance Runners Build an Aerobic Base

For the distance coaches out there, our 40 distance runners run outside every day in rain, sleet, snow, and ice. High winds and cold temperatures are daily. Coach Andy Derks has created a culture where no culture had previously existed. Our distance runners train aerobically with speed work mixed in. Distance coaches build an aerobic base, sprint coaches build an alactic base (unless you are a disciple of Clyde Hart).

Figure 1. Coach Derks came to Plainfield North in 2012. Last year we had 22 guys run under 5:00 in the 1600. Our distance crew makes up about 40% of our track team. The other 60% percent of our team spend their time sprinting with me and lifting with Tim Kane.

The Winter Speed & Strength Format Nov 30 – Feb 4

In the weight room, we strength train Monday through Thursday. I have expressed my lifting philosophy to Coach Kane and he generally agrees.

Our varsity football players lift first, at 2:30. Fifty guys lift as a team. I would rather have all my sprinters in the 2:30 sprint group, but this is a compromise I make.

Coach Kane compromises too. No lifting is done on legs until Thursday. We take Friday, Saturday, and Sunday off. Some people call it a three-day weekend. I call it supercompensation.

Since the varsity football group does not include seniors who have graduated from the football program, my 2:30 sprint group will have some senior football players. In addition, I have freshmen football players, lacrosse kids, baseball players, and, of course, track athletes.

The first session lasts 45-50 minutes, and then our groups switch. From 3:20 – 4:15, I speed train the varsity football team.

On a given day, only 50% of the kids being trained are track athletes.

Winter Speed Training

We start every day with sprint drills, probably the same drills you’ve seen everywhere. As another coach once told me, “Everyone does speed drills, but your kids do them better.” I believe this to be true. We never go through the motions. I refuse to call our opening session a “warmup.” In 17 years of doing this, I’ve never had an athlete get injured doing speed drills. Never. The speed drills done every day include A-skips, high-knees, butt-kicks, 5 box jumps, bounding, straight-legged bounds x2, butt-kick & reach (retro sprints) x2, and starts (2-point, 3-point, or 4-point hop & go). We are done in about 10 minutes.

On Mondays and Wednesdays, we sprint for time. Our field house has a 180m track with a six-lane straight-a-way. We have enough room to run the 55m in an indoor meet. On Mondays and Wednesdays, our kids run 40-yard dashes with a hand-held time. I’ve been doing this for 17 years and can’t give up on my comparative data. Our times are fast because of hand-timing, 2-point starts, and wearing spikes on a rock-hard track. Here is the kicker … we time the last 10m with Freelap (Pro Coach, 12 FxChips). With every run, I record two types of data, 40-yard dash and 10m fly. We run solo. I don’t believe in racing until track season. I want sprinters focused on their fundamentals and competing against themselves. I record, rank, and publish times.

We have two groups, the non-sprint-slow-guys-who-don’t-wear-spikes group, and the speedy-always-remember-their-spikes group. Group-1 is one and done; then they leave the field house. Group-2 runs three 40s.

When coaches hear that we run only three sprints, they are dumbfounded. What? Then what do you do?

“Hard work beats talent when talent doesn’t work hard.” “Nothing worth having comes easy.” “There’s no substitute for hard work.” Coaches are addicted to quotes about work. If the mission of a coach is to get their athletes tired, fine … but don’t expect speed to improve.

Stupid coaches sometimes have the hardest practices. Focus is the key to speed, not hard work.

Figure 2. Don’t be this coach. Train smarter, not harder.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, we do X-Factor workouts. On these days, the football coach joins me. Like always, we do 10 minutes of speed drills. After speed drills, we do four different activities in the form of stations, rotating back and forth between the football coach and me. The only thing I’ve asked Coach Kane … please do things at top speed then allow for enough recovery to go top speed again. The easiest thing for any coach is to get their athletes tired and sore. “Any fool can get another fool tired.” Coach Kane will do agility work, multi-directional sprinting, short hurdles, and speed ladders. X-factor is a day to try new things (“x” stands for unknown). I do wickets, hip mobility, plyometrics, lunges, depth jumps, cat jumps, etc. Since football lifts legs on Thursday, X-Factor is a good way to end the week.

Remember, our program at Plainfield North is based on common ground. Would I prefer sprinting before lifting? Of course. Do I agree with training Monday through Thursday? No. I would prefer Monday-Wednesday-Friday. I am fundamentally opposed sprinters training when they are beaten and battered. We all make deals with the devil, and I will always make deals with football coaches.

Statistics, Data, and Teaching to the Test

My data justified my training philosophy a long time ago. I’ve been doing this for 17 years, and my athletes get faster. More important, talented athletes are attracted to my sprint program.

Data drives my athletes. Low-effort never happens in my speed training. No one forgets their spikes. I literally see my sprinters carrying their spike bag with them in the hallways. Backpack, cell phone, and spikes … the necessities.

At Plainfield North football players run track:

- 28 of our 52 sprinters are football players (54%)

- 9 of our 13 throwers are football players (our throws coach is a varsity football coach)

- None of our 40 distance runners played football last fall

- 37 of our 105 track athletes play football

Plainfield North opened its doors in 2005-06 to only freshmen and sophomores. I became the first head track coach at North in 2006-07. Our first senior class graduated in 2008.

The graph below illustrates our ten-year progress towards creating a culture of speed. I brashly tell people that athletes at Plainfield North know their AFT (Average Forty Time) better than their GPA.

Figure 3. Number of athletes that ran sub 4.60 in the 40-yard dash by year.

Oddly enough, we qualified for the state 4×100 in 2007 in spite our overall lack of speed. It only takes four reasonably fast kids with great handoffs to run a decent sprint relay. If you question our impressive speed numbers, remember … we run hand-held 40’s with a 2-point stance with spikes on a hard track. The numbers are legit. If you time your 40s outside on turf without spikes wearing sweat pants and hoodies, your times won’t be as fast. Personally, I like fast.

In addition, the 40s timed in our winter workouts are always done in the same lane and same direction. Wind is never a factor because we run indoors. I’m the only person who times 40s. No manager or assistant coach will be trusted with the stopwatch.

Why Record, Rank, and Publish?

It’s difficult for some people to understand why we post sprint times. The haters of the world will think we are being boastful. This could not be further from the truth. We simply post times to make times meaningful. Athletes crave competition. Athletes are starved for praise. In addition, coaches must demand quality.

Try this sometime. Tell an 8-year-old to run as fast as he can between two Freelap transmitters (yellow cones). Tell him his time. Then tell him that you will give him $10 if he can run faster. Have several kids cheer him on from both sides of his running lane (we call this “the gantlet”). I am 100% certain you will lose $10.

I did this once in speed camp. I had a young boy who ran several times above 2.00 in the 10m fly. Each time I encouraged him to SPRINT, but his times remained slow. When I attached meaning and significance to his sprinting, he ran faster. His best time improved from 2.03 to 1.57. When you record, rank, and publish, kids learn to SPRINT. Otherwise, kids just run.

Attracting Athletes to Track & Field

Good track programs attract athletes. 24 of my 52 sprinters are newcomers. Check out the average 40 time and average 10m fly time for my top 11 newcomers.

- Wallace Thomas, sophomore, no other sports, first-time track athlete, 4.35, 1.05

- Kevin Block, junior, football, baseball defector, 4.44, 1.05

- Ezra Docks, sophomore, football, moved in this year, 4.51, 1.07

- Nick Wood, sophomore, football, volleyball defector, 4.51, 1.07

- Jaylen Watkins, sophomore, football, didn’t do a spring sport last year, 4.62, 1.10

- Angel Guevara, sophomore, didn’t do spring a sport last year, 4.63, 1.09

- Anthony Capezio, freshmen, football, 4.59, 1.08

- J.D. Ekowa, senior, football star quarterback, 4.65, 1.08

- Burhan Cutlerywala, freshmen, 4.72, 1.08

- Shane McGrail, sophomore, football, baseball defector, 4.68, 1.08

- Zach Nadle, sophomore, football, baseball defector, 4.78, 1.12

When you add eleven guys like this to a good track team, the future looks bright. Kids love a speed-based track program.

Returning Sprinters

We’ve had some bad luck with three of our top sprinters. Tim Donnahue was expected to take one of our sprint relay spots but broke his leg in Wrestling. Our two returning all-state athletes have had some senior bad luck as well. One has a hip-flexor injury and hasn’t sprinted since football. The other, our two-time MVP, has struggled on a daily basis to find food, transportation, and shelter. No one said it would be easy.

Figure 4. We return Zach Shelton (left) and DeVaughn Hrobowski (right) from our all-state sprint relay teams. This picture was taken at Sectional when we ran 42.07 in spite of this run-up handoff at the first exchange. Shelton and Hrobowski missed our winter training. Shelton was injured, Hrobowski spent the winter on the wrestling team.

Despite the bumps in the road, we have seen great improvement in most of our core sprinters. The numbers below indicate their average times last year compared to their average times this year.

- Carlos Baggett, junior, football, 4.46 to 4.28, 1.04 to 0.98

- Clay Pasen, senior, lacrosse, 4.50 to 4.40, 1.03 to 0.99

- Tyler Hoosman, junior, football, 4.66 to 4.42, 1.12 to 1.03

- Cory Hrobowski, senior, no other sport, 4.62 to 4.44, 1.07 to 1.03

- Kevin Block, junior, football, 4.65 to 4.44, 1.09 to 1.05

- Joe Stiffend, sophomore, football, 4.60 to 4.45, 1.04 to 1.01

- Jordan Gumila, junior, football, 4.57 to 4.46, 1.07 to 1.04

- Brian Registe, sophomore, football, 4.48 to 4.46, 1.04 to 1.04

- Hunter Houslet, senior, soccer, 4.71 to 4.51, 1.06 to 1.02

2015 Compared to 2016

The numbers also point out that we are an improved sprint group, at least in sprint depth.

- Last year’s average 40-time of our 25 fastest sprinters was 4.51. This year 4.42

- Last year’s average 10-fly time of our 25 fastest sprinters was 1.05. This year 1.01

- Last year we had five athletes averaging sub-4.50 in the 40. This year we had 13.

- Last year we had 15 athletes averaging under 1.08 in the 10m fly. This year we had 25.

What it Takes to Make Our Sprint Team

We have tryouts for three weeks (Jan 19 – Feb 4). This is what it took to make our sprint group (slowest sprinter from each class, average 40-time and average 10-fly time):

- Freshmen 5.08 and 1.19 (football player and high jumper)

- Sophomore 5.12 and 1.18 (5’10” high jumper as a freshman, scissor-kicked 5’8” last weekend)

- Junior 4.90 and 1.13 (220-pound star linebacker, first year of track)

- Senior 4.78 and 1.11 (football player and hurdler, last year’s times 5.04 and 1.19)

Celebrating Improvement

Data allows us to highlight athletes who show incredible improvement. Celebrating these athletes, in turn, promotes track & field.

Tyler Hoosman is pictured below as a freshman B-team running back. Tyler went out for track his freshman year despite being our slowest sprinter. As a freshmen, Tyler ran the 100 in 13.00, the 200 in 27.9 and long jumped 16’8”. As a sophomore, Tyler obliterated those numbers running 11.92 and 24.38 while long jumping 19’10”. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to project amazing things this spring. Oh, and by the way, Tyler was our varsity’s leading rusher in his junior season. He returns next year.

Figure 5. Plainfield North Running Back Tyler Hoosman as a freshman.

Tyler Hoosman no longer looks like a B-team freshman running back. Tyler now looks like a sprinter. Not everyone will experience the incredible improvement of Tyler Hoosman, but if you don’t measure speed, you will never know.

Figure 6. Tyler Hoosman as a junior. Next year Tyler will dominate.

Run fast to get fast.

Train the alactic system (100% intensity, less than 10 seconds in duration).

Train smarter, not harder.

Recruit, Promote, Attract.

Record, Rank, Publish.

It works for us.

Please share so others may benefit.

[mashshare]

The post Record, Rank & Publish: 8 Weeks of Alactic Training appeared first on Freelap USA.